Overdoses from double dose acetaminophen?

Effect of paracetamol:

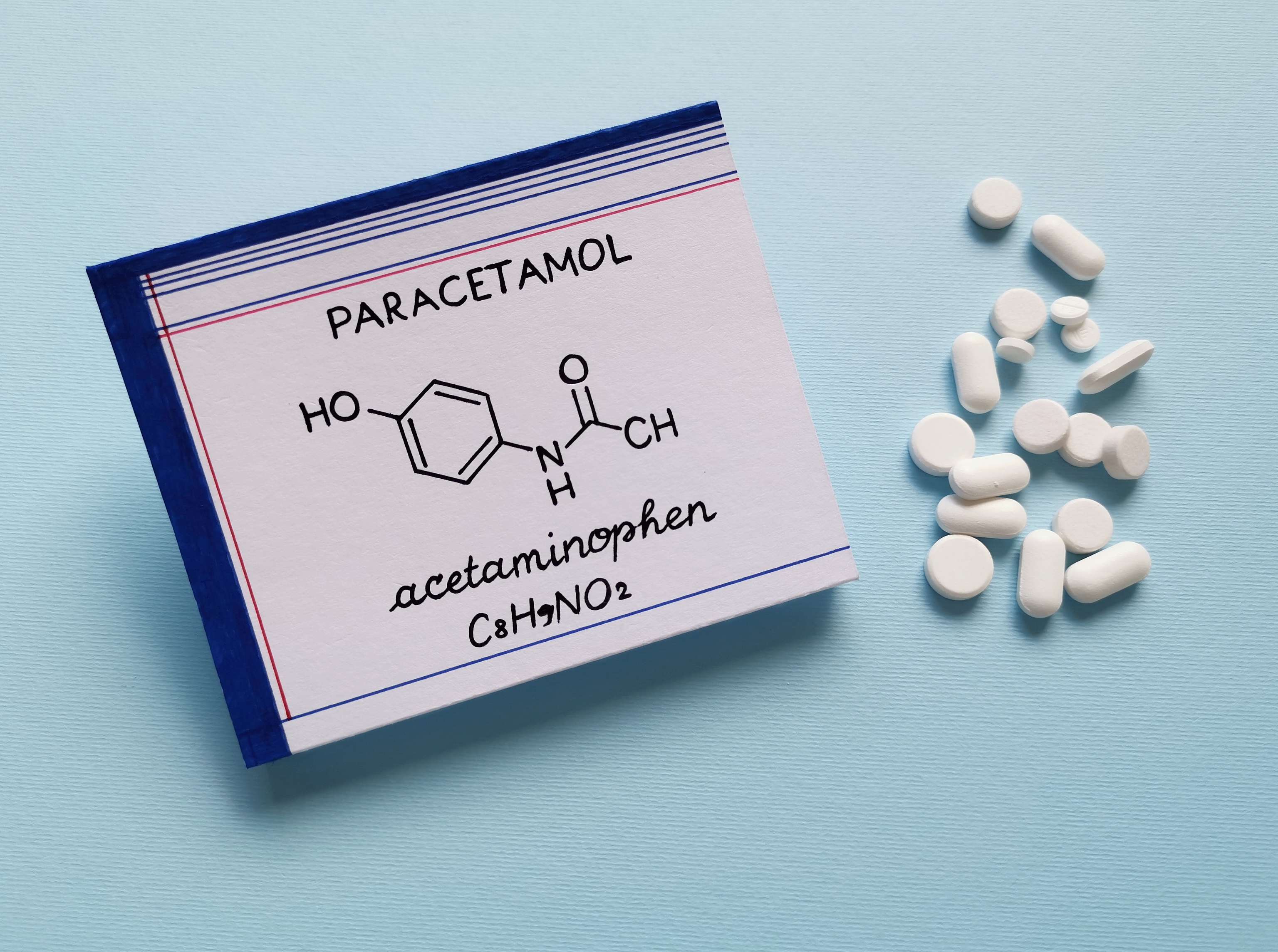

While the well-known active ingredients acetylsalicylic acid and ibuprofen, which are also used as analgesics and antipyretics, belong to the so-called acidic non-opioid analgesics, paracetamol, however, belongs to the non-acidic non-opioid class. This particular acidic non-opioid analgesic species accumulates particularly in acutely inflamed tissues, in the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract and in the renal cortex, and also possesses anti-inflammatory properties. In contrast, paracetamol (known as acetaminophenin North America and Iran) is not primarily enriched in the aforementioned human body regions, but several times in the CNS (i.e. central nervous system - spinal cord and brain). There, a certain enzyme responsible for the production of prostaglandins (i.e. tissue hormones relevant for fever, inflammatory processes and pain mediation) is inhibited by the active substance. Side effects of the non-opioid non-opioid analgesic occur rarely and can usually be attributed to pre-existing underlying diseases. High-dose, long-term use, as well as single paracetamol overdose could possibly cause liver damage, as the liver can no longer function as a detoxification organ. Such possible hepatotoxicity (i.e. liver poisoning) can be caused by taking more than 4,000 mg per day.

While 500 mg tablets are available without prescription in Switzerland, 1,000 mg tablets became available by prescription upon approval in October 2003.

Swiss Study Method:

Although the higher dosage is only available with a prescription, 1,000 mg tablets sold 10 times more than the lower dose as early as 2005, according to the pharmacy association pharmaSuisse.

According to Tox Info Suisse, the national information centre for poisoning cases in Switzerland, there has been an increase in calls to the centre. Even before 2003, the numbers of intentional overdoses had risen, while accidental poisonings remained about the same. Meanwhile, calls for unintentional intoxication are more than 3 times what they were before the high-dose 1,000 mg became available. The number of poisonings involving ingestion of more than 10,000 mg of acetaminophen has also increased.

Previous evidence additionally suggests a possible association between limiting the availability of large doses of paracetamol and a decrease in poisonings associated with the non-acidic non-opioid analgesic.

The Swiss cross-sectional study (i.e., a survey conducted once) used 15,790 paracetamol poison records from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2018, to examine the association between addition of 1,000 mg of paracetamol tablets to the market with the number of poisonings. All acetaminophen poisoning calls identified by the Swiss National Poison Center and all sales of oral acetaminophen tablets (prescription and non-prescription) between January 2000 and December 2018 were included for this study.

The primary outcome was the number of quarterly acetaminophen-related poison calls to the National Poison Center. Additional outcomes included acetaminophen sales per quarter and changes in poison circumstances, which were ranked by pre- and post-intervention periods (i.e., introduction of 1,000 mg tablets) and by dosage (i.e., 500 mg and 1,000 mg tablets).

Results for double dose:

Of the 15,790 poisoning cases identified during the aforementioned 18-year period, 67.3% were women (n=10,628) and the mean age of the patients was 25.2 years. The study period was interrupted and analyzed. Here, the results revealed a significant increase after the intervention point, especially the number of unintentional poisonings. Before the intervention, 15.3% (i.e. 120 out of 961) poisonings had a dose greater than 10,000 mg - in the post-intervention period, 30.6% (i.e. 1140 out of 5696). Sales of 1,000 mg paracetamol tablets saw rapid growth, while sales of 500 mg tablets declined somewhat. Since 2012, an average of 20.7 million 1,000 mg tablets and 2.7 million 500 mg tablets were distributed during the quarter.

A statistically significant change was recorded for accidental but not intentional poisonings. Notably, the proportion of patients with accidental poisonings with an ingestion of 1,000 mg tablets showed an increase as opposed to 500 mg dose in patients with ingested dosages above the therapeutic range of 4,000 mg. Additionally, call data showed that for overdoses greater than 10,000 mg, most reported ingestion of the 1,000 mg tablets.

Conclusion:

With 1,000 mg tablets, the maximum recommended daily dose of 4,000 mg can be exceeded with just a few tablets, and this risk was less with 500 mg tablets. Consequently, the results of the study revealed a significant increase in acetaminophen distribution and acetaminophen-associated poisoning calls in Switzerland following the approval of 1,000 mg tablets in 2003. To minimize a further potential increase in high-dose acetaminophen poisonings, the researchers of this study suggest that the availability of 1,000 mg acetaminophen should be reevaluated. Especially with prescription double dosing, medical information is recommended before use to continue to use acetaminophen with less risk.

Active ingredients:

Sources

- Martinez-De la Torre A, Weiler S, Bräm DS, Allemann SS, Kupferschmidt H, Burden AM. National Poison Center Calls Before vs After Availability of High-Dose Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) Tablets in Switzerland. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2022897.

- Schweiz: Tabletten mit doppelter Paracetamoldosis führen zu mehr Überdosierungen (Ärzteblatt)

- Paracetamol (Netdoktor)

Danilo Glisic

Last updated on 10.05.2021

Your personal medication assistant

Browse our extensive database of medications from A-Z, including effects, side effects, and dosage.

All active ingredients with their effects, applications, and side effects, as well as the medications they are contained in.

Symptoms, causes, and treatments for common diseases and injuries.

The presented content does not replace the original package insert of the medication, especially regarding the dosage and effects of individual products. We cannot assume liability for the accuracy of the data, as the data has been partially converted automatically. Always consult a doctor for diagnoses and other health-related questions.

© medikamio